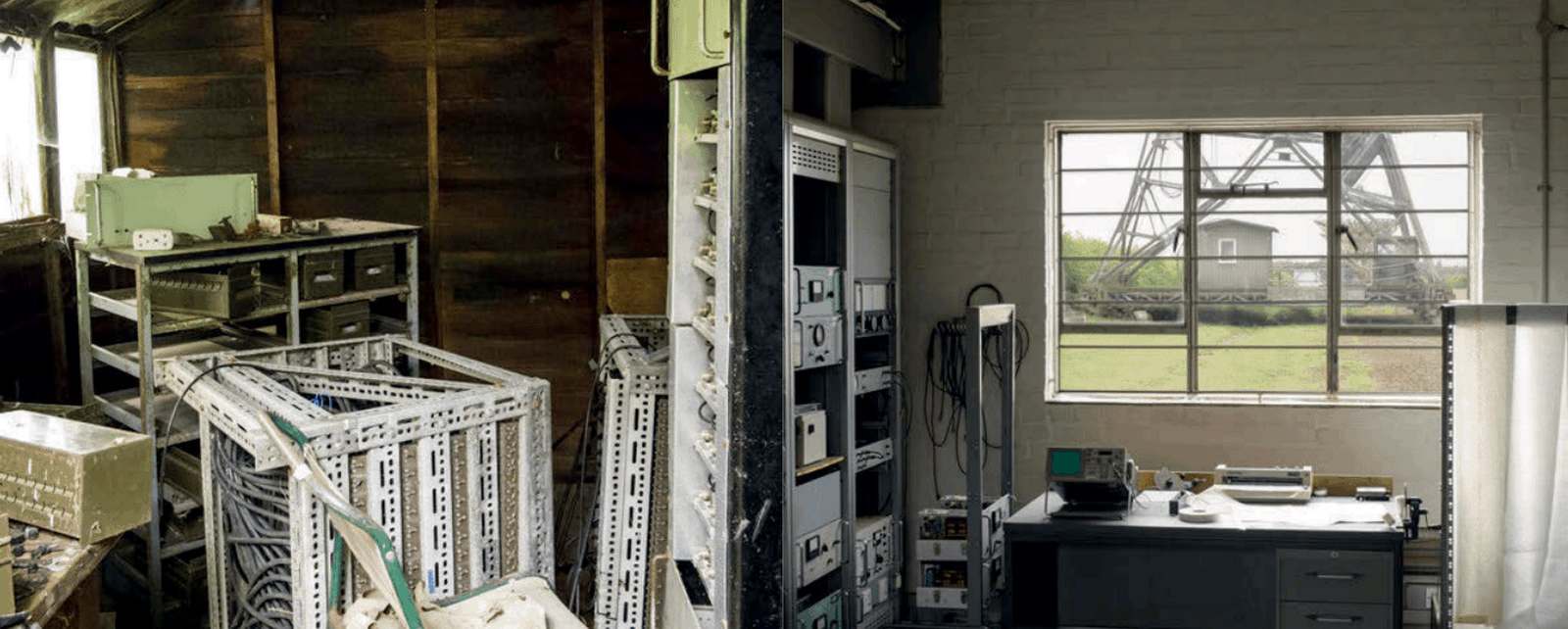

The garden shed where Pulsars were discovered

This article is from the CW Journal archive.

All CW SIGs leverage the SIG champions' very special contacts to access many interesting locations and listen to addresses by industry's leading experts. The Wireless Heritage SIG is no exception and has run trips to the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory, run by Cambridge University's Cavendish Astrophysics Group, twice. Based at Lordsbridge, a few miles west of the city, the site has 150 acres of antennas, control rooms – and history.

While other CW trips may take you to the top of the BT Tower or to research and development labs where work is being done on the future of AI and 5G, the Observatory's highlight is a small, ramshackle garden shed, the place where pulsars were first observed – one of the greatest scientific discoveries of the last century.

The hut is so far-removed from the cathedral of science, which is the Large Hadron Collider, it is hard to fathom.

The shed is linked to a field of dipole antennas which Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who had joined up with Professor Antony Hewish at the Cavendish, was using in her search for quasars. This telescope looks more like a vineyard than a scientific instrument, and, when the Heritage SIG visited, many of Bell and Hewish's dipoles were still in place.

Our guide to the site was Peter Doherty who has been building equipment at the site for nearly 20 years. Steeped in the history of the area and with a passion as much for past endeavours as for the discovery of the unknown, he's one of those people whose infectious enthusiasm comes from being a person who clearly enjoys his work, which must be a prerequisite for working at Lordsbridge.

The site was a station on the Varsity Line, a train service between Oxford and Cambridge that was shut down in 1967, and there are some ominous ghosts in its past – it is probably a dangerous place to be.

During the war the site was a bomb dump, storing munitions for distribution to the local British and US airfields. One of four secret forward filling stations, it stored 2,000 tonnes of explosives, including two 250-tonne containers of mustard gas which was made at the site. After the war, the chemical weapons (which officially never existed) proved hard to destroy by burning.

In an accident in 1955, a 20-tonne tank exploded when a worker on top of it was careless with a blow torch. The accident report says there were no casualties, but a couple of the rescue team were awarded medals, so it is unlikely that the incident was quite as minor as you would 'officially' be led to believe.

Eventually, the munitions were loaded into ships and sunk at sea. Since the war the odd shell has been discovered, so it is unlikely the site is completely clear. As has been found in many dangerous sites, such as Chernobyl, this has been a boon for the local wildlife – and for the radio astronomers of the University of Cambridge, too.

The war had another effect on radio astronomy. The introduction of radar meant a lot of work had to be done to find out how extraterrestrial signals might be proving a distraction to the early warning system. This was highlighted when operators failed to spot three German battleships because of jamming from the French coast. Investigations into which frequencies were involved and where the signals came from led to the discovery of sunspot activity.

After the war, despite funds being limited, Sir Martin Ryle, the great radio astronomer, was able to obtain a large amount of equipment from the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough in Hampshire. Officially, this was bought as army surplus, but Doherty gives the impression that Sir Martin just rocked up at the site with five trucks and helped himself, with no-one minding much. The haul included some captured German radar equipment, including some steerable 3m and 7.5m Würzburg radio antennas.

|

GET CW JOURNAL ARTICLES STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX Subscribe now |

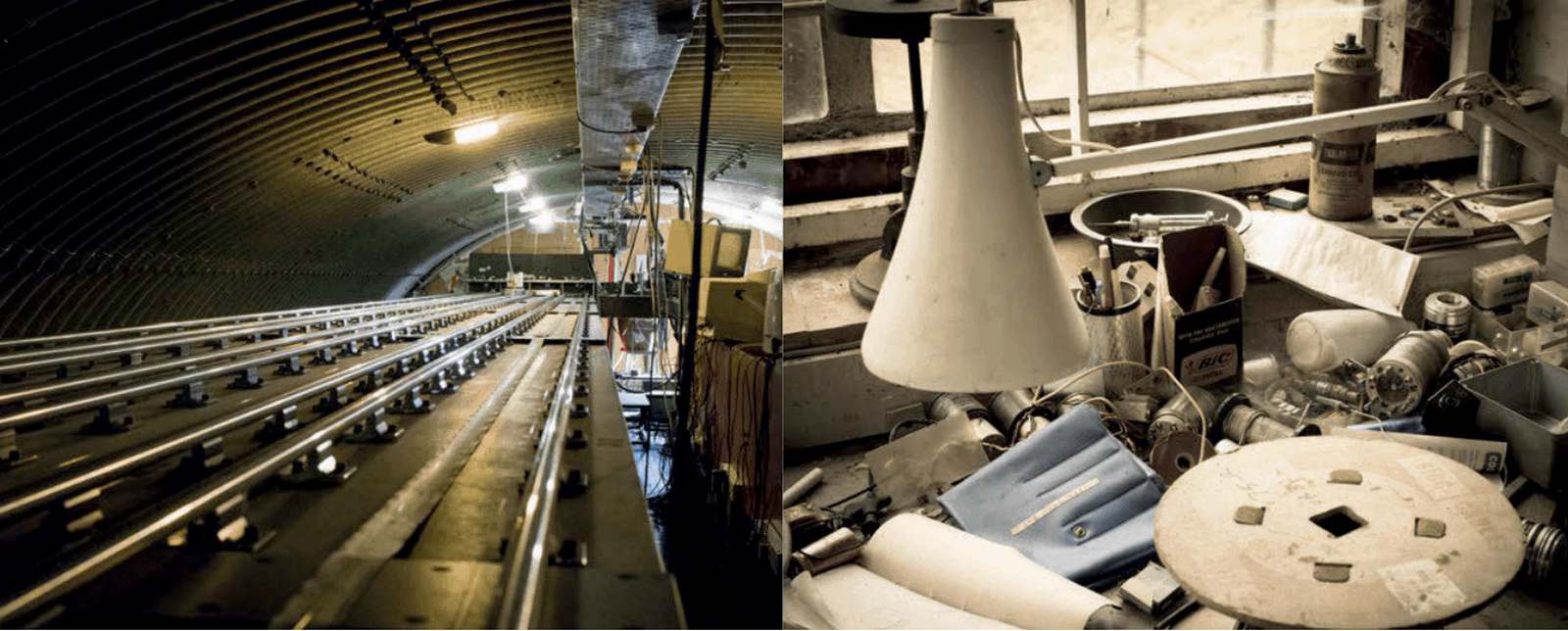

Many of the early telescopes at the Mullard were fixed arrays, using the earth's rotation to scan their 'beams' over the heavens. Later on, the more familiar dishes appeared, which were steerable. A notable feature of the current site are rows of dishes mounted on railway tracks to form aperture-synthesis arrays.

The first telescope to be built at Lordsbridge was the 4C Array, which was the first large aperture-synthesis instrument. It was made up of one fixed and one movable element, with a total length of 450m and a width of 20m. Built in 1957, becoming operational a year later, the telescope used 64km of reflecting wire. It ran at 178MHz and its survey of the sky was completed in 1965, with the results being published in 1965 and 1966.The 4C found nearly 5,000 radio sources and was fundamental in establishing many of the characteristics of galaxies.

When 4C was operational, the Varsity Line was still running and this affected the placement of some parts of the antenna array. The control room for the 4C shows just how important the work was. It includes a viewing gallery where visiting VIPs could watch the astrophysicists going about their business. The site is also home to what are known as the One-Mile and Half-Mile Telescopes. Built in 1964, the larger of the two was the first super-synthesis instrument. Comprising three 120-ton, 18m dishes, two were fixed while the third could be moved along an 800m track to take up station at 60 different points. While the track is straight, one end is raised by 5cm to allow for the curvature of the earth. The telescope operated at 408MHz and 1.4GHz.

The Half-Mile antenna was added in 1968, mainly to make observations of the distribution of hydrogen clouds in nearby galaxies. In 1972, two more 9m dishes were added, one fixed and one on the track. To get a full scan with the antennas in different positions along the track took 30 days.

SINCE THE WAR THE ODD SHELL HAS BEEN DISCOVERED SO IT IS UNLIKELY THE SITE IS COMPLETELY CLEAR

Running mainly at 1.4GHz, the Half-Mile telescope was fantastically productive in its 15-year lifetime, and led to 50 published papers and 20 PhD theses. It was the first telescope to produce good maps of M31 in the Andromeda constellation and M33 in the Triangulum.

Computing systems at Lordsbridge pre-dated magnetic storage, with paper tape being the preferred medium. No actual computing was done at the site, with tapes being taken to the university for processing. The astronomer would configure the telescope by punching a tape with the required coordinates and then take it to the university to use the Edsac or Titan 2 computers. This would result in another paper tape which was taken back to Lordsbridge where it would be used to control the telescope for its run. Signals were recorded on a third tape which was taken back to one of the computers for analysis and to be combined with other results, which were then saved onto magnetic tape.

The control room for the One-Mile telescope feels like a Jon Pertwee era Doctor Who set, with gas discharge clocks and plotters, and a few Eddystone communications receivers. Something notably absent is anything resembling a PC. There are a few oscilloscopes and lots of punching and winding equipment for paper tape. The whole place feels like it is in a timewarp.

In addition to the radio telescopes, there is one optical addition – the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (Coast) which is housed in a former munitions bunker. Like some of the radio telescopes, it uses the Earth's rotation for scanning and a series of mirrors build up the image which is then fed down optical pipes into the bunker, which was covered with earth in the 1980s, to create a stable cool, environment for the complicated optics.

The Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory site is incredible, but it is dwarfed by the awesomeness of what it looks at. Think of a map of the universe with the whole 150 acres of the site as a microscopic dot – and a sign saying: "You are here".

|

GET INVOLVED WITH THE CW JOURNAL & OTHER CW ACTIVITIES |

Simon Rockman bridges writing about technology and implementing it. As the editor of UK5G Innovation Briefing he visits many of the 5G applications. As Chief of Staff at Telet Research he works with a team installing 5G networks in not-spots. An experienced technology writer, he was the editor of Personal Computer World in the late 1980s and went on to found What Mobile magazine which he ran for ten years, and has reviewed over 300 handsets. As the mobile correspondent for The Register, he championed CW writing a number of articles supporting the organisation. He has also had senior roles in telecoms having been the Creative Experience Director at Motorola where he looked at new uses for mobile and Head of Requirements at Sony Ericsson where we worked on innovative devices at entry level. He was the Head of the Mobile Money Information Exchange at the GSMA and has launched Fuss Free Phones an MVNO aimed at older users