The irresistible rise of Bluetooth audio

This article is from the CW Journal archive.

Saying: "Alexa, play the next track," is becoming normal in many households, but if the audio is being streamed to the Alexa device by Bluetooth – and it often is – and the microphone the device is using to listen with is also connected by Bluetooth, then a combination of the audio profile and the headset profile is needed. And Bluetooth can't do this.

For most of the 15 years since Bluetooth first released its Advanced Audio Distribution Profile (A2DP), which standardised a method for streaming personal music, it has been vilified by the media and audiophiles as unfit for purpose. Yet not only has the market for Bluetooth products taken off, you can also find it being openly advertised in serious speakers and systems from top-end audio companies, costing thousands of pounds.

One answer is: "Not much." The original A2DP specification that was released back in 2002 is fairly easily recognisable when you look at the latest versions. Most of the fundamental items of the architecture were there.

Amazon Echo Dot

Devices which constantly listen seem spooky today, but, as with Walkman and Bluetooth headsets, norms change and convenience will conquer the fears of most

But the evolution of products over the subsequent decade has been a good example of how continuous evolution and tweaking can take a standard and an application from something to be laughed at to something universal.

A lot of the early criticism was justified. Not necessarily because of poor specification, but a mixture of practical constraints and some considerable naivety about what’s needed to provide reliable, interoperable, wireless transmission of music. That second consideration may seem odd, given the experience of decades of TV and radio broadcasts, and the more recent growth of mobile telephony, but low power, personal wireless transmission was something new, which brought a whole set of challenges that needed to be sorted out.

It's easy to forget just how good cables are. They have largely unlimited bandwidth, almost no latency, no power requirements, they're pretty secure from eavesdropping, have almost zero development time, are fully interoperable (bar the connectors), and cheap to manufacture. Ironically, the innate ability of even a cheap length of two-core cable to deliver high quality audio spawned a whole industry that tried to make perfectly adequate cables appear inferior by touting pseudo-scientific solutions in the form of ultra-pure copper strands, gold plating and even directionality, which allegedly provided better bass when connected in the marked direction. Audiophiles shelled out millions of unnecessary pounds to comfort themselves in their technical ignorance.

The main criticism levelled at Bluetooth was its lack of bandwidth and the performance of its codec. Bandwidth is largely a wireless issue — a cable carrying an audio signal doesn't constrain the analogue signal it is carrying. With any digital format, where the signal is sampled, the ability to recreate the original signal depends on how often the analogue signal is digitised (the sample rate) and the depth of the sampling, that is, how many bits there are in each sample. The more bits, the greater the resolution, but the flip side is that it generates more data which needs to be transported. The sampling rate determines the frequency range, which is about half the sampling rate. For CDs, the sampling rate is set at 44.1kHz giving a 20kHz frequency range. The resolution relates to the dynamic range of the sound more resolution generally sounds better. Hi-res advocates use 24 bits, whereas MP3 plumps for a more modest 16 bits.

It's evident that digitising can quickly generate a lot of data. A stereo MP3 stream sampled at 44.1 kHz and 16 bit resolution produces around 1.4 Mbits per second. Wireless standards have limited bandwidth. The current Bluetooth audio specification uses a symbol rate of 3 Msps, which equates to a data throughput of just over 2 Mbps. So an uncompressed MP3 stereo stream would take up most of its capacity.

Audiophiles shelled out millions of pound unnecessarily to comfort themselves in their ignorence

This is a problem for a wireless link. Wireless is inherently unreliable, due to interference and fading, so some packets will be lost. That means that any scheme to transmit audio over wireless needs to add in retransmissions to try to ensure the audio gets through. If you're streaming music through your phone, the same 2.4 GHz radio and antenna is probably being used for the Wi-Fi streaming, so the Bluetooth radio may only be available for half the time. As a rule of thumb, the audio shouldn't take up more than 20 per cent of the throughput, so further coding such as MP3 is used to reduce the rate to manageable levels. MP3 has become the most popular codec for music and was designed to compress that 1.4 Mbps stereo stream down to just over 300 kbps, which is fine for Bluetooth.

Despite its popularity, the Bluetooth audio specification doesn't use MP3 – it uses SBC, a low complexity sub-band codec. SBC has similar performance, but was chosen as it doesn't require a licence. To ensure interoperability, the Bluetooth certification process grants a royalty-free licence for all the technology included in the specification. As MP3 was patented and required a licence fee, it couldn't be included as a mandatory option, although manufacturers can choose to include it in addition to the SBC codec.

|

GET INVOLVED WITH THE CW JOURNAL & OTHER CW ACTIVITIES |

MP3 is not the only optional codec. Both MP3 and SBC are relatively old and their patents have expired. In the intervening years, others have emerged and been incorporated in Bluetooth audio products, the most widely used of which are the Advanced Audio Codec (AAC) and the AptX codec, the latter developed by CSR and now supplied by Qualcomm. All of these are "lossy", which means that the decoded signal may not exactly match the original. That has been a point of contention for audiophiles for years, despite the fact that much of their audio material is already encoded with MP3.

At first sight, Bluetooth's limited throughput might suggest it's not the ideal candidate for streaming audio, but other factors come into play. Bluetooth excels at minimal power consumption. It was designed to be low power and it is, compared with its main rival in this area, which is Wi-Fi. Wi-Fi has been successful in static applications which have access to mains power, such as multi-room speakers, but struggles with battery life in devices such as headsets.

Hear no evil

Improving the quality of the Bluetooth link might seem pointless if the source music uses a lossy codec like SBC or MP3, but quality has to be balanced against battery life

Mobility is also another key for Bluetooth. It is universal in mobile devices, and also supports voice for phone calls. It has the key benefit of low latency — important when using it for the soundtrack of a mobile video; and it’s more robust to interference than other wireless interfaces, because of its use of adaptive frequency hopping and power control. That helps a lot when you have a train carriage full of commuters with wireless headsets. There have been other standards attempting to win the wireless audio crown, of which the most well-known is Kleer, but none have moved beyond niche applications.

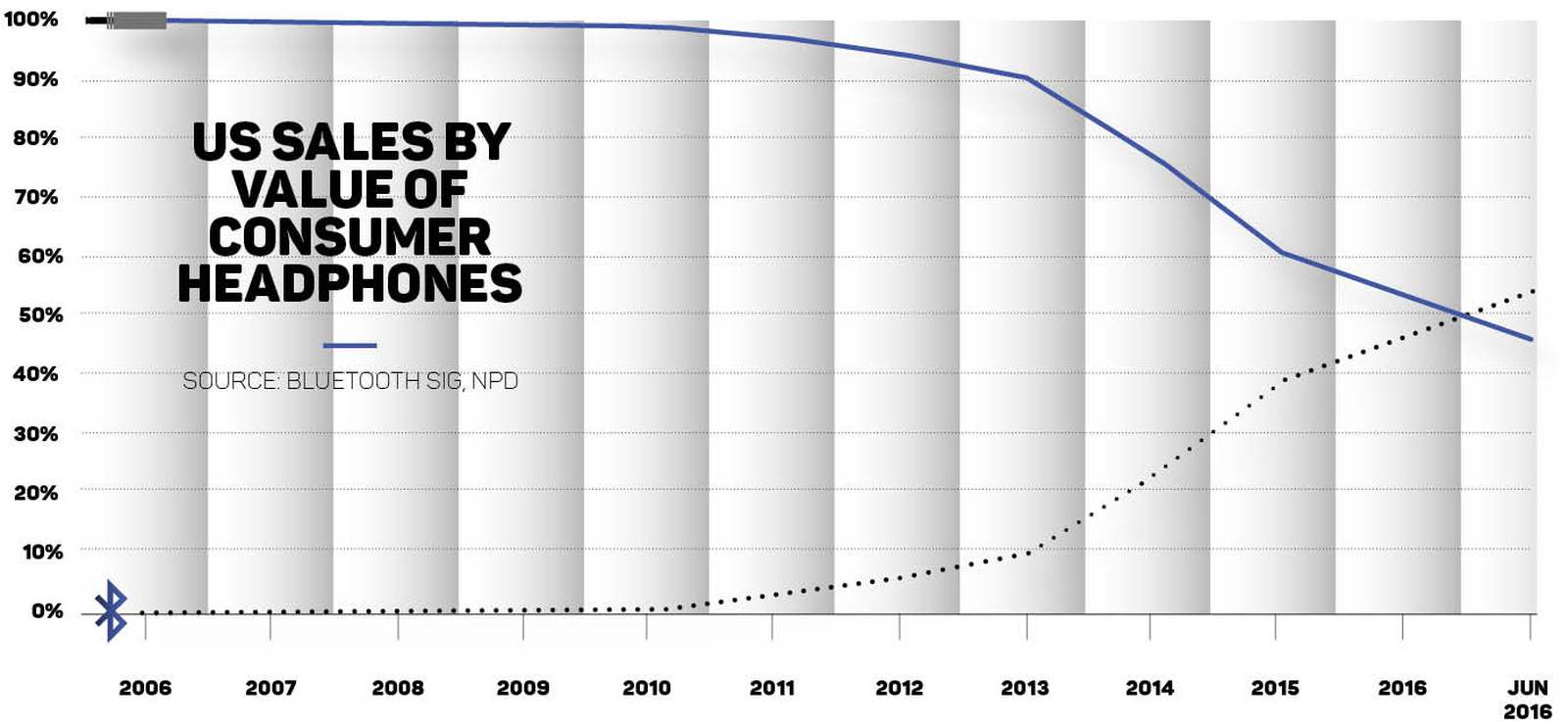

What nobody predicted was the sudden rise in Bluetooth wireless headsets. Improvements in the specification helped to ensure that everybody implemented a competent SBC codec, made clearer what preferred implementations should be, and the arrival of more advanced optional codecs resulted in products which sounded good. Headphones were supplemented by soundbars as audio streaming services took off, but nobody predicted that wireless headsets would become must-have accessories in the run-up to Christmas 2015. By summer 2016, the sales value of wireless headsets in the US had exceeded that for wired headsets. The removal of the 3.5mm socket on the iPhone 7 that autumn accelerated the growth, along with the introduction of Apple's Airpods, stoking consumer demand for wireless audio products.

Qualcomm would like to take some credit for the shift from wires to wireless and says it helped underpin the progression of consumer confidence in Bluetooth through its audio platforms such as Qualcomm aptX which is designed to deliver high quality and CD-like quality audio experiences over a Bluetooth connection. The company told us "aptX has helped contribute to the superior performance in the products of hundreds of household consumer audio brands. When it comes to high definition sound, we are already supporting many audio manufacturers to deliver Bluetooth audio devices that support 24-bit sound quality, using our aptX HD technology." There are more than 55 commercially available wireless devices - headphones, speakers, and receivers – that deliver high-res wireless audio with support from aptX HD. Manufacturers who have adopted aptX include LG, Huawei, Sony, Denon, Pioneer and Sennheiser.

There's still no definitive answer to why this happened when it did. Consumers considered Bluetooth audio quality to be adequate, but there were no significant technical advances in the run up to 2016 that made a step change to performance or desirability. The most likely reason for the sudden uptake was the increasing popularity of larger phone screens and mobile data rates that supported video. Or it could have been the growing acceptance of audio streaming services, along with the social acceptance of wearing over-ear headsets in public. They're both small changes, but technology acceptance is driven by small cultural or usability nudges, not by improvements in the tech itself. This is not to say that the tech hasn't improved. Faster processing speeds in the Bluetooth chips have allowed more effective implementations. Each new generation of silicon has allowed increased the battery life.

By the time you're earning enough to be able to buy these up-market systems, it it questionable whether you'll be able to appreciate the subtlety of their near-perfect reproduction

Meanwhile, transducer design has progressed by leaps and bounds, with better audio reproduction and MEMs based microphones which integrate pre-processing DSPs. As a result, noise cancellation is becoming standard, which certainly helps with perceived audio quality on a noisy commute or in the office. We're also seeing physiological sensors appearing in earbuds aimed at fitness enthusiasts, although that's still a very niche application.

This all means manufacturers of the audio sources such as TVs and phones, as well as headset vendors, have plenty to play with over the next few years. The fact that these products tend to come from different companies makes that an interesting game, as interoperability demands that none can go too far down a proprietary enhancement route if they want their products to work. But we're seeing an explosion of innovation in Bluetooth headsets and earbuds, with features as diverse as health monitoring and live translation.

The Bluetooth SIG is well down the route of completing the next generation Bluetooth audio specification, based on the Bluetooth Low Energy standard. That will offer still lower power, improved audio quality and support for new audio topologies.

Podspeakers MiniPod MKIV

With interesting design and impressive audio quality, these £500 speakers are very much more substantial than simple computer peripherals but have the convenience of no trailing cables

Which brings us back to the high end of the market. Most manufacturers have bitten the bullet and include Bluetooth in their products. Instead of dismissing it, they're accepting it and claiming that their kit can restore the full quality of the source music. Streaming services are trying to push the boundaries of audio quality with more hi-res tracks, encoded at 24 bit/192 kHz, but what the uptake will be is anyone's guess.

Music (and this story is mostly about music) has had a strange effect on users. From a largely social background, where it was shared, it's now something that is increasingly used to isolate people for large portions of the day. It's also increasingly abused. The World Health Organisation estimates that more than a billion people under the age of 30 are already experiencing hearing loss as a result of exposure to loud music. That's an interesting dilemma for the high-end segment of the audio market — by the time you're earning enough to be able to buy these up-market systems, it is questionable whether you'll be able to appreciate the subtlety of their near-perfect reproduction.

Despite our enthusiasm for hearing, we still don't seem to care that much about it. As soon as our sight starts to deteriorate, we go to the optician because we don't like to see fuzzily. But we put up with poor hearing for years before doing anything about it — audiologists reckon that most people put off their first hearing test for at least 10 years. Almost everyone puts quantity over quality. It's just over 60 years since Flanders and Swann took a poke at the audiophile in the Song of Reproduction, pointing out the senseless capability of hi-fi equipment where "…all the highest notes, neither sharp nor flat, the ear can't hear as high as that — still it ought to please any passing bat!". Today, most users are perfectly content with sound reproduction which performs no better than the 1950s products that Flanders and Swann were satirising, which poses an interesting dilemma for the industry.

Despite audiophiles' concerns, Bluetooth has shown that it can meet or exceed user expectations for audio quality, and future specifications will be even better. The bigger challenges are battery life and our growing interest in voice. Voice fuelled the unprecedented growth of the mobile telephony industry as we reveled in the new-found ability to talk to each other wherever we were. The next decade may see that enthusiasm for conversation wane as we start talking to AIs instead of people.

Bluetooth has shown that it can meet or exceed user expectations for quality

Voice will become more important as a technology driver; but as we fall in love with a new-found ability to converse with the internet, it may also spell the demise of the smartphone. To make that happen, we need to see some advances in the standards. Bluetooth has traditionally treated music and voice separately – the A2DP profile is designed for one-way stereo music streaming, whilst voice telephony is handled by the bi-directional Hands-Free Profile (HFP). They were designed as either/or applications, as nobody envisioned that you might use voice control at the same time as you were listening to music. As we start talking to the things we have around us, music needs to coexist with voice. That's a high priority on the Bluetooth development roadmap.

So even if your hearing loss means you can't appreciate the sound quality, you'll still be able to join in the conversation about Bluetooth's merits for wireless audio applications.

For the past thirty years Nick has been closely involved with short range wireless and communications, designing technology that helps to bring mobility to products, particularly in the areas of telematics, M2M, IoT, wearables, smart energy and mobile health. He is closely involved with the Bluetooth SIG, the Continua Alliance and other medical and wireless standards bodies. He is the author of 'The Essentials of Short Range Wireless' - a book attempting to explain the application of wireless technology to product developers.