Digital Twins are in Business

Interested in attending future SIG events? Sign up to CW membership to get free access

Access the slides for the event

Historically both these SIGs have explored the themes of how to put sensors into devices, how to manage communication and how data can be collected. But one of the big issues that the internet of things faces is what to do with the data once it is collected. McKinsey believes that big data can save the world trillions of dollars – the only problem that they foresaw was the shortage of data analysts to process it, and the lack of managers that understand how best the data could be leveraged for the benefit of the business. Digital twins are a potential fix to this challenge. They present an interesting way of visualising data and making it more accessible for managers.

The first talk of the day came from Mark Enzer, CTO at Mott MacDonald and Chair of the Centre for Digital Built Britain (CDBB). He introduced the audience to the idea of the National Digital Twin: an ecosystem of connected digital twins (rather than a massive twin of everything) that, it is hoped, will enable better outcomes from our built environment. The challenge for this project is the collaboration that is needed for all twins to interconnect.

The starting point for the National Digital Twin was a visionary report from the National Infrastructure Commission called “Data for the Public Good”. It recommended that the UK required a National Digital Twin; that in order to facilitate this the country needs an Information Management Framework that supports secure and resilient data sharing and effective information management; to facilitate that it advised the creation of a Digital Framework Task Group with people from across Government, academia and industry to provide the coordination between key industry players.

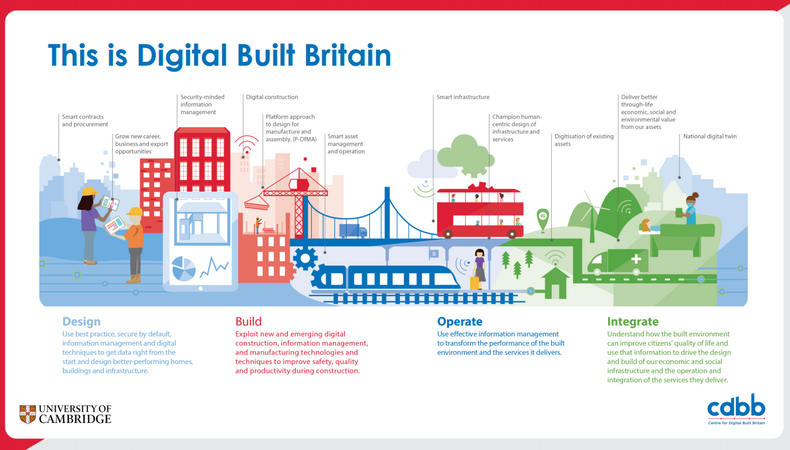

CDBB, a partnership between the University of Cambridge and BEIS, holds the vison of Digital Built Britain (see slide below) and is tasked with delivering the Information Management Framework recommended by the NIC report and aligning industry.

The construction and civil engineering environment is building towards the vision of Digital Built Britain from a strong starting point thanks to the widespread adoption of Business Information Management (BIM) solutions. This technology has had a transformative effect on the “Design” and “Build” phases in the diagram above, but the question now is how companies can unleash that value in the “Operate” and “Integrate” phases. The idea of connecting twins holds a potential answer to extending the impact of BIM as it looks across the whole of the built environment, not just individual assets, and across each of its silos: transport, energy, telecoms, water, waste and social, residential, commercial and industrial infrastructure.

“Each individual silo has its own complexity, but put together we have an amazing system of systems that is essential for the good functioning of society. If that system of systems falls over, so does society.”

However, Britain’s digital infrastructure is not currently managed with this in mind. For the last two centuries the focus has been on building new assets rather than improving the efficiency of those that we already have. Mark had four points to make on this subject:

1. Britain needs to start thinking of its assets as a “System of Systems”.

99.5% of the infrastructure that we need already exists. Each year only an additional 0.5% extra is added. This half a percent comes to approximately 8% of the country’s GDP, so it is nationally important, but if improvements are to be made the country needs to look at the entire 100% of our assets rather than the new 0.5%.

2. Britain needs to consider its assets in terms of the services they provide – a “System of Services”

The system provides the services that enables everything to work. The outcomes of these services are the important factor, not the infrastructure itself.

“If you want to maximise outcomes, what we need to do is focus on the infrastructure and see it not just as a system, but as a system of services…otherwise we might have infrastructure that is very efficient but it feels horrid to use it”

3. Britain needs to recognise the importance of sustainability

The System of Systems must last forever. While assets can follow lifecycles, the system must persist and the ultimate goal is for a full circular economy rather than net zero waste and emissions. And the best way of achieving complete sustainability in our society is to see the problem as a system problem rather than continuing to think in silos.

4. If Britain loves the system, Britain should love the cyber-physical version of that system

Once a systems perspective is adopted, it makes complete sense to deploy a digital version of that system in order to accumulate data and enable stakeholders to make faster, more informed interventions on the built environment.

But to be clear, to generate those more informed interventions, data on its own is not enough. We need to make sense of the data; making sense of the data adds value to it and based on that value we get insights upon which we can make decisions. This is where the digital twin comes in – or more importantly, the National Digital Twin that connects all the insights from individual twins to produce a scenario where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

“At a high level we can define digital twins as a digital representation of something physical; but that’s not quite enough because any model could satisfy that. The thing which makes it a digital twin is the connection to the physical.”

The National Digital Twin is expected to produce societal, economic, business and environmental benefits. These range from more efficient use of tax payers’ money to improved national productivity from higher performing and more resilient infrastructure, the introduction of new markets and new services, and less waste contaminating the natural world.

The concept of the National Digital Twin is admirable. The CDBB is approaching its delivery by creating a highly collaborative environment, working with all stakeholders and establishing a Digital Twin (DT) Hub. The DT Hub is an open, web-based environment where people who are currently developing or deploying twins can share best practice and lessons learned. Current members of the DT Hub include Heathrow Airport, Highways England, Network Rail and London City. The CDBB is also establishing the Commons, a national resource that unlocks effective information management across the industry. The Commons addresses any semantic issues that arise from trying to connect the variety of twins on the market. It offers a foundation data model, a reference data library and integration architecture so that more businesses can create twins in a more consistent (and more easily integrate-able) manner. Finally, the CDBB has produced the Gemini Principles, a set of values that anyone developing a Digital Twin can base their architecture on to create a purposeful, trustworthy and effective twin and ensure that they can be more easily connected up.

Following a talk by Ian Golding, former interim CIO at the Natural History Museum, who presented under Chatham House rules on how this national treasure is deploying digital twin technology to better manage its assets, Paul Green from IoTIC Labs took to the stage to provide more practical guidance on how companies could start to deploy digital twins – even on legacy assets.

Throughout Paul’s experience of connecting devices he has found that the data that is gathered often finds itself, as Mark was discussing earlier, in a silo and unusable by many of the people who could benefit from its insights. Often even the simplest of tasks – reporting a piece of data to an individual so that they can make an intervention – was not happening.

The example Paul gave in support of this point involved train toilets. When a train toilet’s waste tank is full, the door to that toilet is locked and nobody can use it. At the same point in time, a little light comes on in the cabin to signify that the waste tank needs emptying. But it is not the responsibility of the person in the cabin to empty the tanks and so nothing happens. Train operators receive numerous complaints from customers because a week can pass before the waste tank is emptied and the train’s toilet becomes operational again. And all that was needed was the right person to be notified when a light came on.

He went on to explore two more examples of Digital Twins, one from BAM Nuttall and one from Rolls Royce.

As in the toilet situation, the key thing in the BAM Nuttall project was not making sure that a computer knew when a light came on, but that the right people were informed of that situation so that they could take appropriate action. Their construction sites involve a huge number of different stakeholders including, for example, subcontractors and delivery agents, all of whom should have access to certain pieces of information, such as access restrictions. The difficult part of the project was setting up the data collection from the site so that it could be securely and safely shared between relevant parties, or discovered when searched for. This was a semantic challenge that once fixed enabled relationships to be built between the source of data and a potential benefactor.

And once their registry and governance system had been set up, BAM Nuttall was able to redeploy the same digital twin technology in other situations, for example monitoring the presence of safety equipment to accelerate restocking and inform nearby personnel that they need to seek an alternative source of, for example, eyewash.

Another BAM Nuttall digital twin deployment involved waiting for paint to dry.

The key to the success that BAM Nuttall has found is their ability to take data from simple things and share it with safety, security and fearless interoperability. To achieve this, they made digital twins of some sources of data and designed a system where everything can interrelate with a twin of something else. Critically, it is the twins that interact and never the real assets. Sources of data can be classified as to whether they are public (such as a weather sensor) or more restricted (such as details of vehicles on site).

The project was aggravated by a number of complicating factors, one being that construction companies tend not to own their own machinery, they lease it from a company who buys it from the manufacturer. But the data that is produced from a digger on a construction site often bypasses the user and the leaser and goes straight back to the manufacturer. Encouraging machinery manufacturers to share the data with the construction site was a challenge and involved amendments to the full chain of contracts between all parties.

When Rolls Royce started considering how their customers perceive their products, they recognised the urgent need to bring all systems together – not just their internal systems but those of their partners as well, including Hitachi who make the trains, Great Western Railways who run the trains and Network Rail who manage the railway lines. The underlying reason for this transformation was clear – 10-33% of all trains are “off diagram” on any given day due to last minute re-routing, which affects maintenance and servicing, which has a huge knock-on effect on the operation of the railways and the people involved in the system. Simply knowing where the trains are and sharing that information both internally and across all partners had the potential to significantly improve the performance of the railways. Digital twins provided the solution to enabling large corporates, governments and system integrators to access the value delivered by sensors and connected devices in a flexible and scalable manner.

Jonathan Eyre, the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre’s Technical Lead for Digital Twins closed the day with what should have really come at the start of the day: a definition for the technology:

“Live digital coupling of the state of a physical asset or process to a virtual representation with a functional output”

Wherein:

- Live is when state information is available in a timeframe that is close enough to the underlying event. Once a week is as good as thousands of times a second if that’s all the use case requires.

- Digital coupling is the transmission mechanism between data source(s) and data consumption method(s).

- State is the particular condition the physical asset or process is in at a specific time, for example is a door open or closed?

- Physical asset or process is an entity with an existence that has economic, social or commercial value.

- Virtual representation is a analogous description or logical model to its physical asset or process.

- Functional output is information transmitted to a system or human observer that is actionable.

Despite still placing digital twin technology on the peak of inflated expectations, Gartner has research that suggests that 26% of organisations have already implemented a digital twin solution and as many as 59% anticipate implementing digital twin technology by the end of 2020. Initial implementations suggest that organisations that deploy digital twins see the ROI in three years rather than the traditional 10-20 year ROI that is more typical in the manufacturing sector. Earlier in the afternoon Mark had discussed the benefits of the National Digital Twin. Jonathan went into specific examples of benefits discovered from individual supervisory digital twins. These included:

- 50% reduction in unplanned downtime (€ 40,000/minute by German Automotive)

- 40% reduction in maintenance costs (forging line proactively fixing saves $200,000)

- 1%-3% reduction of capital equipment costs

- 5%-10% reduction of energy cost

Finally, the AMRC suggest four steps for businesses looking to adopt digital twin technology.

- Create a strategy for digital twins and review frequently.

- Develop a strategy that uses centralised digital twins linked to relevant applications.

- Investigate overcoming internal skill gaps by outsourcing to IT specialists.

- Investigate digital twins in parallel to IoT and shop floor connectivity. Focus on the current use cases, but understand more connections will be made over time.

CW’s thanks go to all of the speakers and SIG Champions who helped to make this event a success and to PwC’s Cambridge office for hosting us. If you’re interested in attending future CW SIG events, take a look at our upcoming schedule.