The Smartphone Will See You Now: Using AI-backed Devices To Spot Skin Cancer

Skin Analytics, the CW “Discovering Startups” competition winner from 2012, is pioneering the use of AI in medicine: the company is about to start the world’s first clinical trials of melanoma diagnosis using AI.

For now, there's still a human in the loop

Skin Analytics has taken an innovative approach, bringing consultant dermatologist level screening to primary care using a cloud-based service. The service has been rolled out using traditional human dermatologists working remotely, building up the business and routes to market while developing and validating AI algorithms in a large clinical study.

The basic idea is to use smartphones to streamline the diagnosis of skin cancer. Most people who approach their GP with something worrying on their skin will find that it’s an area of medicine where general practitioners are far from expert. Usually the GP will set up a referral, which may mean waiting for some time. If the patient has private insurance the wait will be shorter: if they are insured with the company Vitality, which works with Skin Analytics, there is an even quicker option. Skin Analytics dispatches a dermascopic lens attached to a smartphone to the patient along with easy to follow instructions. The special lens is necessary to acquire a high quality image of the skin lesion for diagnosis: having the highest possible resolution isn’t as important as removing the reflection of light from the surface of the skin.

There is no Skin Analytics app. Instead the image is uploaded to a web portal using a secure login supplied along with the lens. The picture is then passed on to a dermatologist for analysis and a response is typically made in about an hour.

Experience so far suggests that in 60 per cent of cases no further investigation is required. An over-burdened health service or cost-conscious insurer will evidently prefer such a diagnose-at-home solution, and for the patient it’s much quicker and more convenient.

Tackling both hardware and software

Skin Analytics is progressing development on several fronts. It wants to work on a new generation of lens technology, perhaps building its own rather than using the beautifully engineered but expensive systems sold to dermatologists, and it’s also working to augment the human dermatologist with AI.

Skin Analytics founder Neil Daly is very proud of what his company is doing with teledermatology. The AI work is hard, and has necessitated a move from classical computer vision to more advanced techniques of deep learning. The team has spent a lot of time looking at data sets, but appreciates that you need to handle it in the right way.

People kid themselves about how well AI works, because they are over-fitted to the data.

The Skin Analytics AI system is written in Python on the Theano framework. It’s been built by Jack Greenhalgh, whose PhD was in vision systems for cars. Much of what he learned has gone into the Skin Analytics work. One of the problems Skin Analytics faces is lack of training data for the AI: pictures of moles also need to be accompanied by data on the conditions the picture was taken under, demographic information for the patient and biopsy results. In the long run, this won’t be a problem: with 132,000 new cases of melanoma diagnosed worldwide each year, the scale of the problem is also the route to the solution.

For now, however, getting a good enough data set is a big issue for Skin Analytics.

“A big part of my PhD work was based on trying to recognise road signs,” explains Greenhalgh. “Gathering real data for 350 different types of road sign and getting enough images of all of those – especially the obscure ones – was very difficult. But the system needed to recognise even the obscure signs in order to order to avoid misclassifying them.”

“The way we went about doing this was to completely synthesise the training data. We just created graphical templates which were then augmented in order to build the training set. This sort of data augmentation is something we’re now using heavily for melanoma detection.”

The augmentation is a very important part of the process. It’s vital to know which augmentations work, which don’t and which are realistic. Skin Analytics has found that symmetry is an important part of detection, as cancerous lesions are generally asymmetric. Augmentation which creates symmetry destroys useful information.

There are advantages as well as challenges in this application, however. Skin Analytics doesn’t have to process its images in near real time as is required in automotive vision. The company hosts the processing itself using CUDA on graphics cards.

To err is human. To admit uncertainity is AI

Skin Analytics’ actual AI uses the traditional system of having a number of classifiers which produce a confidence level. Part of the special IP of the Skin Analytics solution is the way it uses the data to train the classifiers and the way the classifiers are ensembled. Greenhalgh tells CWJ that his system is already at a level as accurate than a human: but more importantly there is a score on the accuracy. The AI knows when it probably isn’t accurate and reveals that, an advantage over human dermatologists.

“There are a lot of nondeterministic elements in the way that data is fed into the into the classifier,” says Daly. “So every time you train you get a different result at the end. The system learns so many different things: then when you put them all together the mistakes tend to get averaged out.”

AI systems need to recognise obscure things to avoid misclassifying them.

Skin Analytics has already found that the software is picking up information from data that is unexpected: it makes correct classification decisions from changes to the data which should not immediately be expected to yield more information. But Daly cautions that producing a real-world working system is not simple.

“People kid themselves about how well AI works, because they are over-fitted to the data,” he says, noting that IBM has spent five years researching melanoma AI without any service yet launched.

Nonetheless Skin Analytics says that its AI is comparable in accuracy to human dermatologists, with an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) greater than 0.9, but the upcoming clinical trials will really prove its worth. This takes in six hospitals and over 1,000 patients, and Daly and his team are tense but quietly confident.

It’s been quite a journey for Skin Analytics. Daly says that winning CW’s Discovering Startups was really good for the company, getting it widely known and attracting business partners.

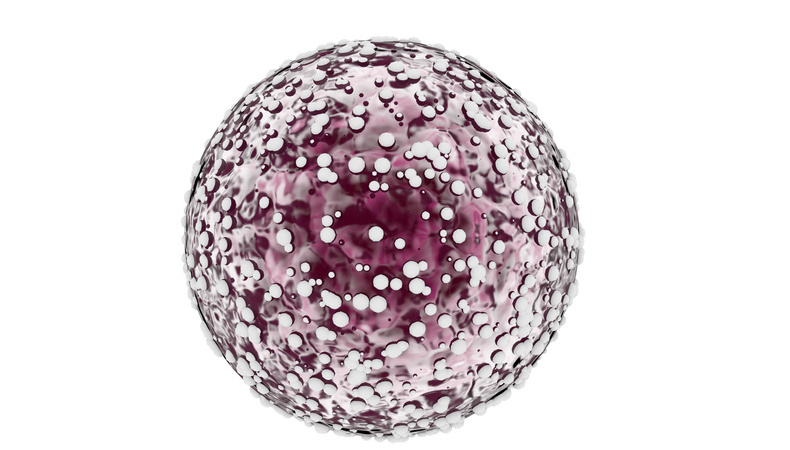

Skin Cancer: Melanoma is a cancer of melanocytes, cells which produce the pigment melanin. Melanocytes can also form moles, where diseased melanocytes like the one picture above, may develop into a melanoma.

Simon Rockman

Publisher, CW Journal

Simon is an experienced technology writer and was Editor of Personal Computer World in the late 1980s and created the world’s first consumer magazine about telecoms, What Mobile. He has held senior roles at Motorola, Sony Mobile, and the GSMA. He is also founder of Fuss Free Phones, a unique MVNO catering for the needs of older people.

Continue the conversation on Twitter. Follow us on @cwjpress and use hashtags #cwjournal and #skinanalytics

Pg 14-15